Filmed in New Jersey

Micheaux’s movies, including many filmed in Fort Lee, showed African-Americans in all walks of life.

Oscar Micheaux, the pioneering film director of Black American cinema, produced more than 40 movies in his lifetime, and a handful of his pictures were made, at least in part, in Fort Lee, New Jersey.

Oscar Micheaux, the pioneering film director of Black American cinema, produced more than 40 movies in his lifetime, and a handful of his pictures were made, at least in part, in Fort Lee, New Jersey.

After completing his first movie, The Homesteader, in Chicago, Micheaux headed to Fort Lee in 1919 to film Within Our Gates, which silentfilm.org reports “was produced on a $15,000 budget from an original screenplay written by Micheaux himself.” Many interpret the film as a response to The Birth of a Nation’s glorification of KKK violence four years earlier. Whether or not that was his intent, Micheaux used this and other films to demonstrate the effects of racism.

Patrick McGilligan, writing for the New York Times in 2007, noted that Micheaux’s movies “were among the first films in history to attack lynchings, segregated housing, gambling rackets, corrupt preachers, domestic abuse, criminal profiling by police, and all kinds of racial inequities.”

Ten years later, Svetlana Shkolnikova of the nj.com website assessed that “while white filmmakers often characterized African-Americans as entertainers or domestic workers, Micheaux sought to paint a more nuanced portrait of the African-American experience and showed black actors in every social stratum.”

In a New Yorker review of a recent screening of Within Our Gates, writer Richard Brody stated: “Oscar Micheaux’s bold, forceful melodrama, from 1919—the oldest surviving feature by a Black American director—unfolds the vast political dimensions of intimate romantic crises…With a brisk and sharp-edged style, Micheaux sketches a wide view of Black society…and the harrowing ambient violence of Jim Crow, which he shows unsparingly and gruesomely. Along with his revulsion at the hateful rhetoric and murderous tyranny of Southern whites, Micheaux displays a special satirical disgust for a Black preacher who offers his parishioners Heaven as a reward for their unquestioning submissiveness.”

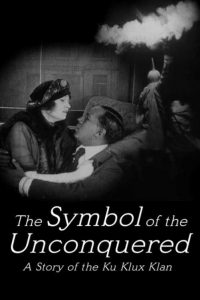

Micheaux returned to Fort Lee in 1920 to film The Symbol of the Unconquered which, 99 years later, was finally screened in the town where it was filmed. On this occasion, the Barrymore Film Center website observed that the picture is “a ground-breaking film in that it depicts the Ku Klux Klan as a terrorist organization as opposed to director DW Griffith’s portrayal of the KKK as saviors in his 1915 film Birth of a Nation. Micheaux, in shooting this film in 1920, was using the same streets and locations in Fort Lee as Griffith did some 8 years earlier when he was shooting his Biograph shorts on location in Fort Lee.”

It wasn’t until 1931 that Micheaux returned to Fort Lee to film The Exile, a movie that borrowed from his life in South Dakota. The Exile was the director’s first talkie and is considered the first sound film in Black cinema.

Beginning in 1940, Micheaux spent eight years away from filmmaking, returning to his craft in 1948 for what would be his final movie, The Betrayal. Except for some location shooting in Chicago, the film was shot at a studio in Fort Lee.

The Betrayal premiered at the Mansfield Theater in the Broadway district of New York City and earned its director his only review from the New York Times. Afterward, the movie played to Black audiences in theaters in the South.

LeRoy Collins, one of the actors in the movie, told Film Quarterly in 2004, “when they showed The Betrayal throughout the South, the lines formed for blocks outside the theaters…You have to realize that in this time period Blacks could not go to white theaters throughout the South and various other areas, or they could go only on certain days—like only Wednesdays—so Mr. Micheaux rented those theaters after the regular performances were over, at nine or ten o’clock at night, and that’s when The Betrayal would be shown. That was a hurdle he had to leap…”