Cue the Chorus

In coming weeks, nature's symphony will include Brood X cicadas as they emerge from 17 years underground.

One person’s idea of a noisy racket is another’s favorite rock band. By and large I have a real aversion to noise. On the other hand, I’m a sucker for natural phenomena. So when one of nature’s extravaganzas involves noise I try to adjust my mindset and find it awesome versus dreadful. But I’ll admit our subject creature challenges my auditory sensitivities. A few are fine, but a crowd is a 1960s spacecraft hovering. In fact the sound made by these creatures are by magnitude almost two times louder than a vacuum cleaner’s 70 decibels (dB), beating city traffic (80 dB); alarm clocks, hairdryers, chainsaws (100 dB), power lawnmowers (110 dB), sandblasting and most rock concerts. Measured at 130 decibels, they are tied with a jackhammer. We are speaking of the cicada.

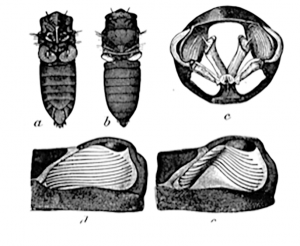

Yup, that’s right, that wall-eyed little bugger, with its two-inch wings, all by itself can create about 85 decibels while serenading, but in chorus they can produce a crazy din. The metallic rattle comes from the tymbal, an organ on the male’s side, just behind where the wing is hinged to its body. The very rapid clicking is made by vibrating this membrane. Most of the bulbus posterior of the insect is hollow and acts like a drum to amplify the sound.

The female’s clapping wings can be imitated by snapping one’s fingers together. A great BBC internet video shows Sir David Attenborough seducing a male cicada by snapping his fingers along the length of a branch, causing it to head toward the sound. By clicking first in front of and then behind the cicada he gets a response much like a duck in a shooting gallery as the insect continually switches directions toward his snapping fingers.

In 2004 my husband and I went to Bevan Wildlife Management Area, not far from Shaw’s Mill Pond, to witness the spectacle and experience the explosion of sound produced by the insects. Listening to the cicada calling evoked one of my rare mortality moments, and I began to tear up. My husband looked at me quizzically. I explained, “Well, I’m wondering how many more times I will hear this 17-year brood.” To which he reminded me that many of my forebears made it into their 90s. But in fact my parents’ lifespan would indicate that this year might be my last chance to hear what is popularly called the 17-year locust. STOP. These are not locusts, these are cicadas. People call them 17-year locusts because locusts appear in a huge group and swarm. STOP AGAIN. Cicadas don’t swarm and they don’t really eat leaves either. But they appear with remarkable simultaneity and in a very large cohort, and that is where mystery and amazing intersect.

Entomologist Dr. Sam Ramsey, when interviewed on NPR’s Shortwave, remarked that some areas will have 1.5 million cicadas per acre. Gene Kritsky in his new book Periodical Cicadas, The Brood X Edition, states that Brood X was documented in Philadelphia in 1715. He also found an earlier record of cicada in a Plymouth Pilgrim colony in 1633.

They occur in 15 states including New Jersey, and Brood X is the largest of them all. The 13-year cicada, also Magicicada, is prolific but not like Brood X. There are other species that occur at different intervals. Brood X Magicicada includes three species—septendecim, cassini, and septendecula. Could you be hearing these species in other years? Yes, but in smaller numbers. There are off-schedule emergents called stragglers; typically 17-year periodical cicada stragglers emerge four years early while 13-year stragglers arrive four years late.

All three species look pretty much the same to the untrained eye, although septendecim is larger. Septendecim and cassini can be distinguished by ear, since septendecim’s call is a “wee-oh” or “phaaaaroah” while the chorus is a drone, and cassini is a thrum with clicks and in chorus is more of a buzz. Septendecula is said to be rare and few choruses are heard; individuals make “tss’s,” “zips” and “ticks.” I would suspect our critters in 2004 were primarily septendecim, creating the UFO sound.

Most articles and news stories are simply going to call all these species Brood X cicadas. And frankly after wading through the differences, I’m realizing their wisdom.

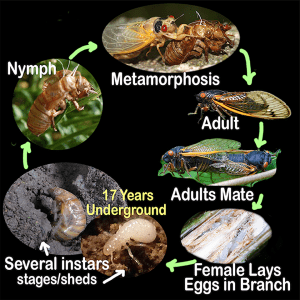

To better understand what is going on let’s discuss their lifecycle—their circle of life. I’ll begin with the final larval stage emerging from the ground, after 17 years of a solitary existence clinging to a root while sipping “xylem sap” about 18 inches beneath the soil’s surface. Xylem sap is the dissolved minerals in the tree’s circulatory system that carries nutrients to the leaves. The liquid aspect is lost through transpiration, which is the process by which trees release water vapor into the air.

So for 17 years the cicada nymphs are attached to a tree root just hanging out. Apparently they do not harm the tree in this stage and rarely move. When the ground reaches about 64 degrees, they surface nearly in unison, likely in late April or early May. The nymph is in its final stage or instar at this point and uses strong front legs to emerge from the ground. It climbs a tree trunk and metaphorizes into the adult insect, leaving behind its exoskeleton, or casing. Sometimes these sheds remain clinging to the bark, or they fall to the ground in large heaps when they are abundant.

When the adult first emerges from the exoskeleton it is rather tender and white-ish. Then in a few hours it dries. The body transforms into a rather heavy black bullet-shaped creature, with clear orange-veined wings and wide-set red eyes (and three additional “simple” eyes that you are not going to notice).

After 17 years of hanging out beneath the ground they have only one thing in mind—sex. The male sings, the female clicks her wings, and they mate. As with most lifeforms the goal is to ensure the future of the species. As adults they live only four to six weeks.

After mating the female uses her ovipositor to saw a crevice into a branch and deposit her eggs. She generally places 20 eggs in a location but ultimately may lay 600! The sawing open of the branch is pretty much the only harm the tree suffers. Older trees tolerate the pruning, but young trees don’t always fare well. Arborculturalists recommend, in areas where 17-year cicada are common, that nurserymen hold off on any plantings a year prior to known emergences.

Six to eight weeks later the eggs hatch. A pale ant-sized nymph falls to the ground. This nymph will have five instars or sheds before its final nymph stage, the one that will emerge 13 to 17 years later, climb, and transform into the adult.

There is a mystery about how the cicada marks time. Dr. Chris Simon, a molecular systematist at University of Connecticut’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, and Gene Kritsky, an entomologist at Mount St. Joseph University in Cincinnati, Ohio, call their time-keeping ability an internal molecular clock. They believe it is linked to the seasonal changes in xylem fluid, the sap on which they feed. James Heath published a study in 1968 where he demonstrated that accumulated ground temperature triggered their ascent from beneath the soil. But they don’t emerge whenever the ground reaches that temperature so they also have to count years.

What is the advantage of coming out all at once? Dr. Sam Ramsey explained it as predator satiation, “a fancy way of saying you can’t eat all of us.” This allows for a large number to survive and successfully reproduce. Which brings up the question, “What eats cicada?” Other insects, birds, squirrels, bats, amphibians, fish, reptiles, and even people. The glut of cicadas often causes some of their predators to change their eating habits in a large brood year.

People say they taste like shrimp with an asparagus flavor but remember they have many stages and some are not as delectable as others. Nymphs first coming from the ground before hardening are said to be the tastiest. Once they transform into adults and their wings begin to stiffen they’re apparently no longer so scrumptious. No, I do not know this from personal experience!

The Onondaga Nation has a history of survival linked to the cicada. They are one of five tribes linked to the Iroquois Confederacy and their present-day territory is south of Lake Ontario in Onondaga County, New York. In 1779, being burned off their properties through an order given by George Washington was one of many abuses they suffered. The devastation of their crops and villages left them in a famine state from which the cicadas saved them. Today a number of Onondaga still consume cicada, comparing the taste to popcorn, bacon, and even crab (New York Times).

I suggest leaving consumption to the more adventurous or knowledgeable. At least do your homework but also consider that cicada play a role in the ecosystem, adding nutrients to the soil and providing food for many animals. Probably many of their benefits are yet to be revealed.

My interest in a cicada meal pales in comparison to my curiosity to learn more about them. If you’d like to access a website that is a portal to all things cicada, check out Cicada Mania where the most avid curiosity can be quenched!

Sources: American Association of the Advancement of Science (AAAS), magazine

Cicada Mania

Penn State Extension, College of Agricultural Sciences

Thermal Synchronization of Emergence in Periodical “17-year” Cicadas 1968.

Animal Diversity Web

New York Times, June 2018