Within the past week, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy issued Executive Order 124, which authorizes the DOC Commissioner to furlough certain inmates to home confinement from state prison due to the Covid-19 pandemic and the threat posed to those in prison, including officers. I’m not the betting sort, but if I were, I’d bet that this EO stirs a strong range of responses.

Within the past week, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy issued Executive Order 124, which authorizes the DOC Commissioner to furlough certain inmates to home confinement from state prison due to the Covid-19 pandemic and the threat posed to those in prison, including officers. I’m not the betting sort, but if I were, I’d bet that this EO stirs a strong range of responses.

Some will be vehemently opposed, pointing out the risk to public safety, the potential for more Covid-19 carriers, and burdens on the system. Others believe that if Covid-19 takes hold in that type of institutional setting, it will spread like wildfire with a high body count.

Note that this is not a random or haphazard release of prisoners back into the community. EO 124 sets out a fairly robust and thorough review process for an inmate to get a furlough to home confinement. The process involves a series of lists to be vetted by the State Parole Board and an Emergency Medical Review Committee.

The first tier to be considered for furlough is inmates 60 years old and older with underlying medical conditions. The second tier of inmates for consideration is those 60 years old and older without medical conditions or other ages with underlying medical conditions. The next tiers include those serving a prison sentence with either their maximum release date or parole eligibility within 90 days of the date the list is generated.

Once these lists are created, they go to the Director of the Division of Criminal Justice and to the County Prosecutors, who must notify victims or next of kin about the possibility of a home-confinement furlough. Then the prosecuting agency gets to weigh in with the parole board and the Emergency Medical Review Committee as do victims or next of kin, where applicable.

Once this process for the emergency medical lists is completed, the parole board will expedite hearings for parole-eligible inmates with first consideration given to those on the first list and then the second tier, and so on down the line.

A furlough to home confinement assumes that inmates have a home to go to or a community sponsor providing a place to be, and a supervision plan that includes social services where needed. For many, this also involves telephonic check-ins or electronic monitoring, a special ID they must carry, and other measures.

The issues surrounding inmates and Covid-19 are not simple or one-size-fits all. For older people and those with medical conditions, Covid-19 could well be a death sentence no matter what side of the bars they’re on so it should matter that the people who might make one of these lists didn’t commit crimes worthy of such a penalty.

This also involves the issue of racial disparities, because if Covid-19 sweeps through the prison population, it’s going to be mostly black and Latino impacted or dying—blacks represent 14 percent of the state population, 55 percent of the state’s inmates whereas whites are 59 percent of the state population and 25 percent of the state’s inmates.

I understand the concerns surrounding public safety, which is why local officials have strongly opposed the transfer of inmates from facilities in other parts of the state into our region. As for the older people being considered for home confinement, it helps to recall that older people (i.e. 60 and older) do age-out of crime.

As for healthcare in prison, inmates have $5 co-pays for whatever care they receive. That’s in line with what some folks pay on the outside, but if you’re earning 26 cents an hour at a prison job, you’ve got to work some 19 hours to cover one co-pay. Thankfully, co-pays have been waived for Covid-19 related care in prison.

Given the breadth and scope of this pandemic, what to do about the incarcerated is not an easy thing and it wasn’t when the issue was county jail inmates. The easy decision is to let the chips fall where they may in prisons and jails since inmates are an unsympathetic bunch, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s the right decision.

COVID-19 and Inmates

Some will be vehemently opposed, pointing out the risk to public safety, the potential for more Covid-19 carriers, and burdens on the system. Others believe that if Covid-19 takes hold in that type of institutional setting, it will spread like wildfire with a high body count.

Note that this is not a random or haphazard release of prisoners back into the community. EO 124 sets out a fairly robust and thorough review process for an inmate to get a furlough to home confinement. The process involves a series of lists to be vetted by the State Parole Board and an Emergency Medical Review Committee.

The first tier to be considered for furlough is inmates 60 years old and older with underlying medical conditions. The second tier of inmates for consideration is those 60 years old and older without medical conditions or other ages with underlying medical conditions. The next tiers include those serving a prison sentence with either their maximum release date or parole eligibility within 90 days of the date the list is generated.

Once these lists are created, they go to the Director of the Division of Criminal Justice and to the County Prosecutors, who must notify victims or next of kin about the possibility of a home-confinement furlough. Then the prosecuting agency gets to weigh in with the parole board and the Emergency Medical Review Committee as do victims or next of kin, where applicable.

Once this process for the emergency medical lists is completed, the parole board will expedite hearings for parole-eligible inmates with first consideration given to those on the first list and then the second tier, and so on down the line.

A furlough to home confinement assumes that inmates have a home to go to or a community sponsor providing a place to be, and a supervision plan that includes social services where needed. For many, this also involves telephonic check-ins or electronic monitoring, a special ID they must carry, and other measures.

The issues surrounding inmates and Covid-19 are not simple or one-size-fits all. For older people and those with medical conditions, Covid-19 could well be a death sentence no matter what side of the bars they’re on so it should matter that the people who might make one of these lists didn’t commit crimes worthy of such a penalty.

This also involves the issue of racial disparities, because if Covid-19 sweeps through the prison population, it’s going to be mostly black and Latino impacted or dying—blacks represent 14 percent of the state population, 55 percent of the state’s inmates whereas whites are 59 percent of the state population and 25 percent of the state’s inmates.

I understand the concerns surrounding public safety, which is why local officials have strongly opposed the transfer of inmates from facilities in other parts of the state into our region. As for the older people being considered for home confinement, it helps to recall that older people (i.e. 60 and older) do age-out of crime.

As for healthcare in prison, inmates have $5 co-pays for whatever care they receive. That’s in line with what some folks pay on the outside, but if you’re earning 26 cents an hour at a prison job, you’ve got to work some 19 hours to cover one co-pay. Thankfully, co-pays have been waived for Covid-19 related care in prison.

Given the breadth and scope of this pandemic, what to do about the incarcerated is not an easy thing and it wasn’t when the issue was county jail inmates. The easy decision is to let the chips fall where they may in prisons and jails since inmates are an unsympathetic bunch, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s the right decision.

Related Posts

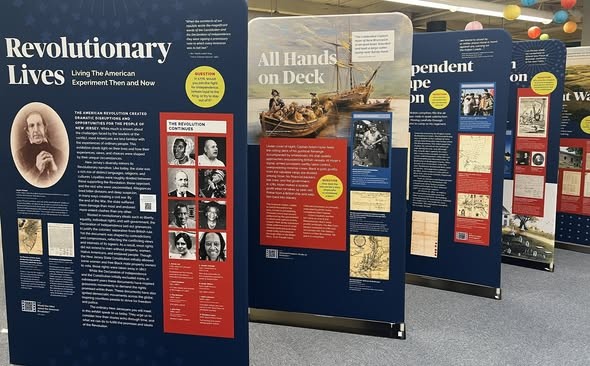

Exhibit To Travel to Millville

Household Hazardous Waste and Document Shredding Events Set

Pep Rally at VHS is Superintendent’s Sendoff

Blue Skies Forever Tour at The Levoy

Newsletter

Be the first to know about our newest content, events, and announcements.

Mayoral Musings

Vineland’s Glastron To Expand

Nationally Ranked Vineland Fighter in Big Bout March 28

Millville Army Air Field Museum Welcomes Pangburn to Advisory Board