Cause for Celebration

New Jersey prepares to de-list the American bald eagle after decades of recovery efforts.

Our nation has a number of iconic national symbols—our flag, the national anthem, the Liberty Bell, a national motto: “In God we trust,” Uncle Sam, the Statue of Liberty, and our national tree and flower, the mighty oak and the rose. The Great Seal of the United States displays the American bald eagle, with a scroll in its beak inscribed with our original Latin motto, “E Pluribus Unum,” meaning “one for many” and referring to the original union of 13 colonies. In the eagle’s talons are olive branches and arrows, representing peace and war. We could also talk about many other symbols of America like Mt. Rushmore, or the Pledge of Allegiance.

In honor of the upcoming Fourth of July holiday, I’m going to focus on two of our national symbols—our national bird, the American Bald Eagle—and mammal, the North American Bison. The first of a two-part series, this week I will discuss the eagle and its recovery in New Jersey, while the following week we will focus on our great Western symbol of endurance, strength, and dignity—the mighty bison.

For a number of years the Endangered and Nongame Species Advisory Committee has recommended the de-listing of the American Bald Eagle in New Jersey because of the great success of the recovery program here. The process of listing and de-listing rare species takes a long time but the eagle recommendation is now at the public comment stage, meaning the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) has posted a rule proposal and is listening to feedback on that proposal through August 2, 2024.

The June 3, 2024 DEP press release for de-listing reads as follows:

“The de-listing of eagles and ospreys is a milestone in the history of wildlife conservation in New Jersey and is a testament to the dedication of DEP professionals and volunteers who over the years stood watch over nests in all forms of weather, nurtured hatchlings, and worked tirelessly to educate the public about the importance of sustaining wildlife diversity,” said DEP Commissioner Shawn M. LaTourette.

“Because of their efforts, people across the state today can thrill at the sight of bald eagles gliding above their massive tree-top nests or ospreys diving into a coastal creek to snare a fish,” LaTourette continued. “While we celebrate these successes, we must remain vigilant in ensuring that these species continue to thrive and be ever mindful that endangered species continue to need our help.”

“The recovery of these species from near extirpation during the 1980s in New Jersey is a dramatic example of what is possible when regulations, science, and public commitment come together for a common purpose,” said David Golden, assistant commissioner of NJDEP Fish & Wildlife. “With focused attention on other species of greatest conservation need, future recovery success stories are also possible.”

Under the New Jersey Endangered and Nongame Species Conservation Act, which celebrated its 50th anniversary this past December, NJDEP Fish & Wildlife’s Endangered and Nongame Species Program (ENSP) is responsible for protecting threatened, endangered, and nongame species.

The proposed de-listing of bald eagles and ospreys is made possible by work ENSP has implemented over the years with the help of many partners and volunteers that resulted in steady increases in the populations of these species, increases that became particularly pronounced over the past 10 to 15 years.

Today, bald eagles can be found in virtually every area of the state, with their highest numbers occurring along Delaware Bay, rich in protected marshlands and coastal creeks that provide ideal habitat.

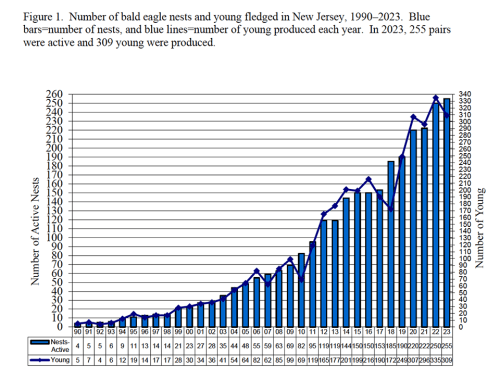

In 2023, New Jersey boasted a record 267 nesting pairs of bald eagles, of which 255 laid eggs. In the 1970s and into the early 1980s New Jersey had just one remaining bald eagle nest, a pair in a remote part of Cumberland County. The state’s population had been devastated by widespread use of DDT and other threats, including habitat degradation and human disturbances.

Once used widely to control mosquitoes, DDT is a synthetic insecticide that had lasting impacts on the food chain, accumulating in fish that eagles eat and causing them to lay thin-shelled eggs that could not withstand the weight of the parent birds during incubation. The federal government banned DDT in 1972, marking a pivotal step in the ultimate comeback of the species.

Recovery efforts in New Jersey began in the early 1980s, with reintroduction of eagles from Canada as well as artificial incubation and fostering efforts that started to pay discernible dividends throughout the 1990s. Active nests surpassed 100 for the first time in decades by hitting 119 in 2012. Ten years later, the total had more than doubled to 250.

“The recovery and de-listing of bald eagles and ospreys is a huge milestone for our state,” said ENSP Chief Kathy Clark. “Many people have worked for years and decades to bring these species back from the brink, including biologists, volunteers, and all those who protect and steward habitat for rare wildlife. This is an achievement for all those who work on behalf of the natural ecosystems of New Jersey.”

The federal government removed the bald eagle from its list of endangered species in 2007, reflecting strong gains in the population throughout the nation. The current bald eagle protection status in New Jersey, however, remained state-endangered during the breeding season and state-threatened for the non-breeding season, reflecting caution about nest disturbance and habitat threats. Under the rule proposal, bald eagle status will be changed to species of special concern.”

I remember in the late mid-1980s only one eagle’s nest remained, in Bear Swamp, Downe Township. This nest had six consecutive years of nest failure before state biologists decided to intervene. In 1982 they removed an egg for artificial incubation at Patuxent Wildlife Center in Maryland. An artificial egg was left to allow the adult to continue its incubation efforts—a ruse—and then the fostered hatchling was returned to the nest. DDT, although banned in 1972, still remained in the female’s reproductive system, thinning her egg shells such that they were not strong enough to withstand the rigors of normal incubation. The fostering program continued successfully until 1989 when a younger female took the previous female’s place. At that point the eggs could be hatched without human assistance.

In conjunction with these efforts, the Endangered and Nongame Species biologists also began a hacking project in 1983. This involved moving older chicks from Canadian nests and completing their rearing at the Glades Wildlife Refuge and Tuckahoe Wildlife Management Area. These birds imprinted on our region and stayed to raise more eagles, ultimately contributing to the increase in nestling success that occurred from 1990 onward.

Protected habitats and monitoring have proven to be significant keys to the success of this program.

As of June 5, 2024, 38 chicks have fledged this season and 283 hatched chicks have been reported. Some nests are obscured by foliage such that chick reports are difficult or impossible.

Over the years much knowledge has been gained through nest monitoring and maintaining records. The need to monitor nests will continue into the future. After delisting it is still important to look for population changes.

In fact, many animals with abundant populations exist below the threshold of study and even census. Then if—or when—a population crash takes place, there are no baselines to compare their pre-crash numbers with the current tally. One of the best examples of this is the often-cited tragic decline of vultures in India. When vultures’ numbers plummeted there, the cause was a mystery until an anti-inflammatory medicine was found to be the culprit; the medicine was fed to cattle and vultures ate the carcasses, drastically affecting the population. Since no one knew what the original numbers had been when they were nearly extirpated, no one knew what restoration, if accomplished, would look like. As this makes clear, population counts and monitoring of even common species have merit.

The restoration of the American bald eagle in the lower 48 states and the bison to the American West are considered to be the greatest conservation achievements of all time. Next week we will look at the story of the bison.