Bison: At Home on the Range

Read here about one of the greatest conservation success stories of all time.

The American bald eagle and the bison are official symbols of our nation, and both species are linked to the greatest conservation success stories of all time. This week we continue our two-part story, focusing on the bison.

At 2,200 pounds and six feet tall the bison is North America’s largest land mammal. It is estimated that before the arrival of colonists their numbers in the Great Plains were 30 million to 60 million. By the early 1900s, after decades of modern hunting as compared to Native Americans’ far lower harvest of the animals, the number had dwindled to a mere 1,100 animals.

President Theodore Roosevelt and William Hornaday recognized the plight of the bison, informally and mistakenly called “buffalo,” and in 1905 they and other Americans established the American Bison Society in an effort to save them from extinction.

As an iconic symbol of the American West, bison hold significant importance to our nation. They have appeared on our currency, and almost continuously since 1917 the symbol on the Department of Interior’s seal has been the bison. It shifted to a design featuring an eagle from 1923 to 1929, but it has depicted a bison ever since (except in 1968-1969). The Wyoming state flag proudly displays the bison, and legendary figures such as Buffalo Bill have adopted its name. Black men who were enlisted to help protect westward expansion by building roads and participating in military actions like the Red River War (1874-75) and the Spanish American War (1898) were called Buffalo Soldiers. On May 9, 2016, the American bison was named the national mammal.

The Department of the Interior reports that it manages 17 bison herds on public lands, totaling some 10,000 bison in 12 states, including Alaska (2022). Yellowstone Park is the only place in the U.S. where bison have lived since prehistoric times and that herd, estimated to be 5,450, is the largest population on public lands.

Ancestors of modern-day bison existed in southern Asia thousands of years ago. The ancient land bridge that connected Asia to North America was their route of passage during the Pliocene Epoch 400,000 years ago. Those ancient animals were larger, with horns that measured nine feet from tip to tip.

While I’m from New Jersey, I’ve had the privilege of observing bison on many occasions, primarily in Yellowstone but also in New Mexico and other states.On a trek not far from Hayden Valley in Yellowstone, my husband and I hiked a few miles from the trailhead on a cool fall morning. It was a wide dirt path. Along the trail to our right was a tall berm that ran parallel to the trail.

I paused and asked, “Do you hear that? It’s like the ground is alive!”

There was a deep bass tone—a natural resonant frequency that vibrated in our chests and that I could feel in the soles of my feet. It seemed nearly like synchronized breathing. I decided to climb the berm to peer over the top. As my eyes came even with the highest point along the berm I saw the heavy condensation produced by the exhalations of a lounging herd of buffalo; my eyes were level with theirs. This was literally a “holy cow!” moment. I was struck by both their majesty and the danger I had placed myself in.

As lumbering an oaf as a resting bison may appear, they can run 35 miles per hour and also easily jump a car or gore a person if they so choose. Knowing I can do neither—jump or run, that is, but reverse is in my repertoire of actions— I retreated to report my findings in the best out-of-breath whisper I could muster: “Yes, a whole herd! Lots of ’em. Let’s move on now!”

About a quarter mile further along the path we heard what sounded like large tires being pounded together—a huge muffled thud. Eventually the source became evident. There was a circle in which male bison “bulls” were pounding heads; we were above them on a hill looking only a short distance down. They were completely absorbed in this activity; it was clearly a “lek,” where an aggregation of about eight males was slowly pacing around in a circle. Two would break away from the group and meet in the middle, and at about six feet from one another they would proceed forward to pound each other in a horrid crash of their foreheads.

It seemed that watching bison from the roadside, high above Hayden Valley in the late afternoon, would be a safer vantage point than the trail we had chosen. We also passed hot mud baths where buffalo bones were all that was left of one boiled ungulate. Perched on the high ridge of the valley from a parking area I saw some bison ascending toward us. With a long lens I decided to take some face-on snaps. Evidently one bison was into photo ops and decided to step up its pace toward me. I scrambled to the far side of a car and noticed many other folks had congregated to view the buffalo as well. While I was intently looking through my lens this had escaped me. Then the thought struck me that a person who was threatening the bison was far more likely than I, who was giving way, to get in trouble. Fortunately he decided to meander all of us.

One of the things I enjoyed most in my bison observations was watching them taking massive dust baths—called wallowing. When they wallow and roll in the soil it creates a huge dust bowl; this is apparently to deter biting flies and help shed fur. They increase dust-bathing during mating season, likely to mark territory. Males begin mating at six to 10 years of age while cows (female bison) begin mating at two and have just one calf at a time. Bison live up to 20 years of age.

The 19th century westward expansion by Americans and their lust for bison was not sustainable. Overhunting and habitat loss were the demise of the herds. By the late 1800s only several hundred existed in the wild.

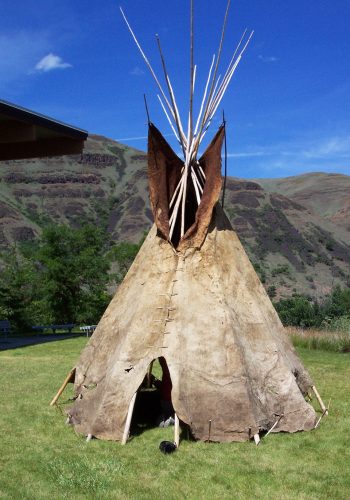

Conversely, Native Americans made use of bison products for hundreds of years but their hunting methods did not threaten the population. They used projectile points instead of guns to harvest game and every part of the animal was put to use, not just for food but for clothing, shelter, and implements. The Department of the Interior’s museum program documents the many tribal uses of these animals.

Bison and the culture surrounding them were an interwoven way of life. Bison hide was used for tipis, a critical nomadic shelter. Ceremonial headdresses were made from the fur that covered the skull of the animal. Pelts were donned when hunting them. Waterproof rawhide was used for satchels, bags, and drum heads. Horn was submerged in hot water until supple, after which it could be crafted into tools, utensils, weapons, and adornments. Coats, robes and blankets were fashioned from fur hides.

Today bison roam both “public and private lands.” There are approximately 500,000 throughout North America; their history is one of the greatest conservation success stories of our time. n

Sources:

- Smithsonian, Many Lenses Series, Buffalo Soldiers, Legend and Legacy, National Museum of African American History & Culture. (website: Nmaahc.si.edu)

- U.S. Department of the Interior, 15 Facts About Our National Mammal: The American Bison. (doi.gov)

- American Bison: A National Symbol, Learn how the once endangered bison transcends history as an enduring aspect of Native American cultures and thrives as part of our shared heritage. By the U.S. Dept. of Interior Museum Program.