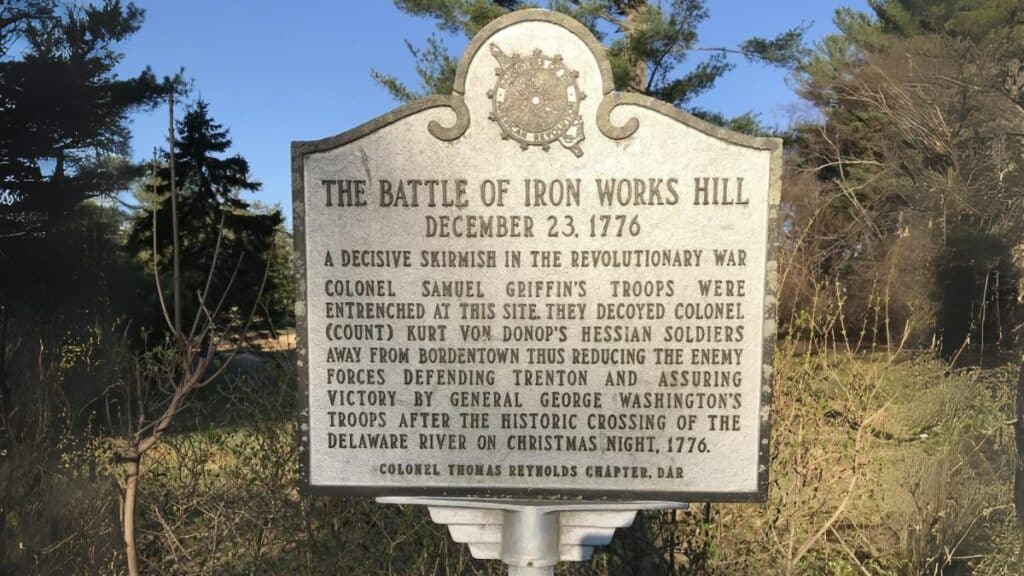

How the Battle of Iron Works Hill Secured Washington’s Success at Trenton

The Battle of Iron Works Hill, fought in the fading days of December 1776, occupies an odd space in the annals of the American Revolution.

Overshadowed by Washington’s dramatic crossing of the Delaware and his decisive victory at Trenton, this skirmish in Mount Holly seems, at first glance, to be a minor episode in the larger narrative of the war.

Yet, as historians have dug deeper into the chaotic events of that winter, they have come to realize that what happened on Iron Works Hill was far more consequential than the casualty numbers or troop movements suggest.

This is not the story of a triumphant victory or a devastating defeat; rather, it is the story of how distraction, miscalculation, and even the peculiarities of human behavior shaped the course of history.

The winter of 1776 was a bleak one for the Continental Army.

Washington’s forces had suffered humiliating losses throughout the fall, retreating from New York and crossing into Pennsylvania with their numbers and morale shattered.

Disease and desertion had reduced the once-imposing army of 20,000 men to a pitiful remnant of 3,000, most of whom were hungry, cold, and contemplating the expiration of their enlistments.

The British, by contrast, seemed on the verge of total victory.

They had secured New York and established a string of garrisons throughout New Jersey to solidify their hold on the region.

The Hessians, German auxiliaries hired by the British, manned many of these outposts, including the strategically vital town of Trenton.

Sitting at a critical point on the Delaware River, Trenton was both a forward position for the British and a dagger pointed at Philadelphia, the heart of the rebellion.

Colonel Johann Rall commanded approximately 1,400 troops stationed in Trenton, while five miles to the south, Colonel Carl von Donop held a larger force of 2,400 men in Bordentown.

Von Donop’s command included Hessian grenadiers, jagers, artillery units, and the renowned 42nd Highland Regiment, a Scottish force that brought discipline and ferocity to the field.

Together, Rall and von Donop formed a formidable barrier to any American attempt to retake New Jersey.

It was in this grim situation that Washington launched one of the most audacious plans of the war.

Knowing that his army could not survive another defeat, he took the offensive.

His target was Trenton, and his plan called for a surprise attack on the morning of December 26 after a risky night crossing of the Delaware.

But Washington faced a daunting logistical problem: even if his attack succeeded, reinforcements from Bordentown could quickly overwhelm his forces.

Washington needed a diversion to prevent this, and that task fell to Colonel Samuel Griffin.

Griffin was an officer with the Flying Camp, a short-lived militia force whose command consisted of about 600 men, most of them young, untrained volunteers.

The plan was not for Griffin to win any major battles but simply to harass the enemy and keep their attention away from Trenton.

Griffin’s small force crossed into New Jersey and moved toward Mount Holly, a town perched along the Rancocas Creek.

On December 21, they made their presence known by attacking a Hessian outpost at Petticoat Bridge, about three miles north of Mount Holly.

The Hessians fell back, but the attack was less about causing damage and more about planting the idea that a significant American force was operating in the area.

Colonel von Donop took the bait.

Reports reaching him described Griffin’s force as numbering in the thousands, and although this was wildly inaccurate, it played into von Donop’s preconceptions about the Americans.

He believed that the rebels had a habit of exaggerating their numbers and bluffing their strength, but the possibility of a real threat near his position could not be ignored.

Leaving Bordentown on December 23 with nearly his entire command, von Donop marched south to confront Griffin.

The fighting began at Petticoat Bridge, where Hessian and British troops easily pushed back the Americans, who retreated into Mount Holly.

The Americans made a stand at Iron Works Hill, a rise south of the Rancocas Creek, where they had hastily constructed defensive positions.

They exchanged fire with the advancing Hessians from here, but their inferior numbers and lack of artillery made the position untenable.

Griffin’s men quietly slipped away as night fell, retreating toward Moorestown.

At this point, von Donop could have returned to Bordentown.

His objective—to chase Griffin’s force from the area—had been achieved, and his position at Bordentown remained critical to supporting Trenton.

Yet he chose to remain in Mount Holly, which would have far-reaching consequences.

Several factors likely influenced von Donop’s decision.

One was the inaccurate intelligence he had received, which led him to believe that Griffin’s force was much larger than it actually was.

Another was the condition of his troops.

After days of marching and skirmishing in freezing weather, they were eager for rest, and Mount Holly offered the first opportunity in weeks for the entire force to encamp together.

But there is also a more human, perhaps more compelling, explanation.

Von Donop took up quarters in the home of a young widow, who Hessian Captain Johann Ewald described as beautiful and captivating.

It’s possible this woman was a patriot sympathizer or a spy, and her presence seemed to hold von Donop in Mount Holly longer than prudence dictated.

As von Donop lingered in Mount Holly, Washington was putting his audacious plan into motion.

On the night of December 25, the Continental Army crossed the Delaware under brutal conditions, with freezing winds and floating ice threatening to derail the operation.

By the early morning of December 26, they reached Trenton and launched a surprise attack on the Hessian garrison.

Colonel Rall, caught off guard, was unable to organize an effective defense.

Within an hour, the Americans had captured nearly 900 Hessian soldiers, killed dozens, and inflicted a blow that revitalized the rebel cause.

By the time von Donop received word of the disaster at Trenton, it was too late.

His force, still encamped in Mount Holly, was in no position to respond.

Washington’s victory at Trenton marked a turning point in the war. It boosted American morale and secured much-needed support from soldiers and civilians.

Though small in scale, the Battle of Iron Works Hill played a decisive role in this outcome.

By drawing von Donop away from Bordentown, Griffin’s ragtag force ensured that Trenton would remain isolated, and the significance of this cannot be overstated.

Had von Donop remained in Bordentown, he could have marched to Trenton within hours, and the outcome of Washington’s attack might have been very different.