Looking at Glass

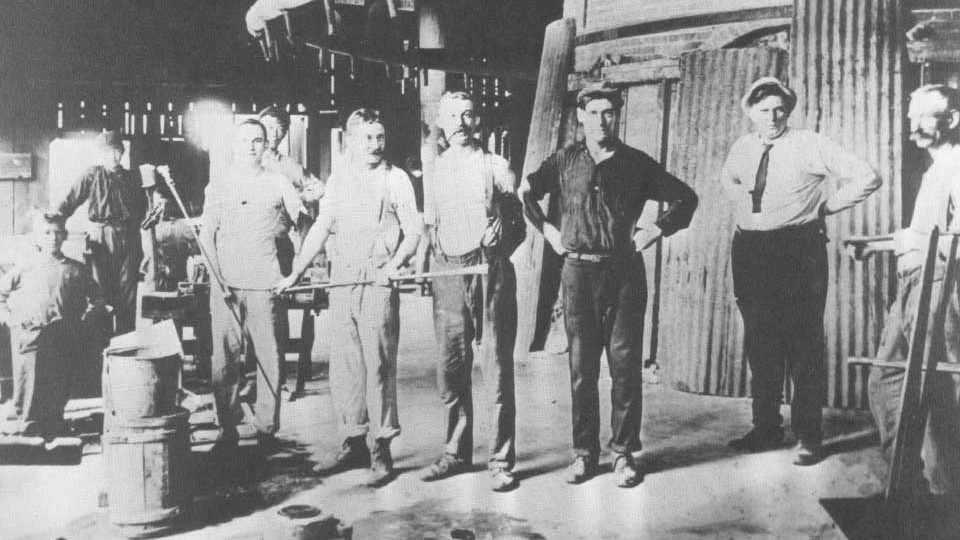

Glass factories once supported many local families as part of a major business in our region.

Did you know that America’s first successful glassworks was started in 1739 by Caspar Wistar, a German immigrant, in the tiny town of Alloway in Salem County? Yes, glassmaking had been attempted previously in other regions, such as Jamestown, Virginia, but it took a visionary who saw that South Jersey had everything he needed to make his new venture a success.

Did you know that America’s first successful glassworks was started in 1739 by Caspar Wistar, a German immigrant, in the tiny town of Alloway in Salem County? Yes, glassmaking had been attempted previously in other regions, such as Jamestown, Virginia, but it took a visionary who saw that South Jersey had everything he needed to make his new venture a success.

Wistar enlisted skilled glassblowers from his homeland to work in the factory. And thanks to the Pine Barrens, which then sprawled across the lower portion of the state, his glassworks had more than sufficient fuel for furnaces that usually roared at least six days a week. The silica sand found here, with its high iron content, resulted in the creation of a green glass (later known as “Jersey green”) that was used for sturdy bottles and a variety of tableware.

In operation for close to 50 years, when Wistarburg went out of business it is very likely that many of the glassblowers there moved to other locations where the industry was just getting started. Towns such as Salem, Bridgeton, Millville, Glassboro, Hammonton and later, Vineland, soon recognized that glassblowing was destined to become a major industry in the region. By the end of the 1800s, there were more than 200 glass factories in New Jersey—most of them located in the southern portion of the state.

Bottles, jars and tableware quickly became a staple for many companies but the talented glassblowers were permitted to indulge their creative sides when the workday ended. Using any leftover batch (as liquid glass was known), they produced colorful canes and small animal figures, which would be dubbed “whimseys.” The Jersey lily, although classed as a whimsey, was actually made at the start of the day before production began. It was a way to test the batch to see if it was ready for blowing.

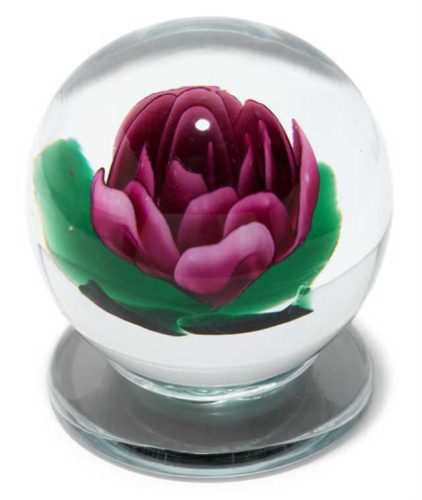

Paperweights became another creative outlet for local glassblowers, who originally copied the cameo figures and flower form known as “millefiori” (thousand flowers) produced in Europe. A new uniquely American form of paperweight was born around the turn of the 20th century that became known as the “Millville Rose.” It was probably first made by Ralph Barber, a talented local craftsman who inspired later generations to try their skill at glassblowing. Like the whimseys, paperweights were often given as gifts to family members and friends.

Another prized type of glassware created in South Jersey was the Art Nouveau glassware created at the Vineland Flint Glass Works. Victor Durand, Jr., who owned the company in the early 20th century, was determined to create something besides bottles and other functional glassware that had been a staple of the business for many years. With the assistance of Martin Bach, Jr., a former designer for Tiffany, he encouraged the glassblowers he hired to create dazzling, jewel-like decorative ware, as well as tableware, lighting fixtures and perfume bottles that immediately attracted public attention.

Sadly, the division was only in operation until 1931 when the economic crash in America meant that most people could not afford to buy such pieces. Although the Kimble Glass Company purchased the Vineland Flint Glass Works after Durand’s death in 1931, the art glass division soon folded as interest in their products waned.

This is just a small sample of the stories still waiting to be told of the glass companies in South Jersey, an industry that supported many local families for generations. Although the number of factories still in operation are a fraction of what they once were, they keep alive the spirit of those early glassmakers.